Sweet and Sophisticated: The Story of Tokaji Wine

- 20 July 2016

- Celia Hay

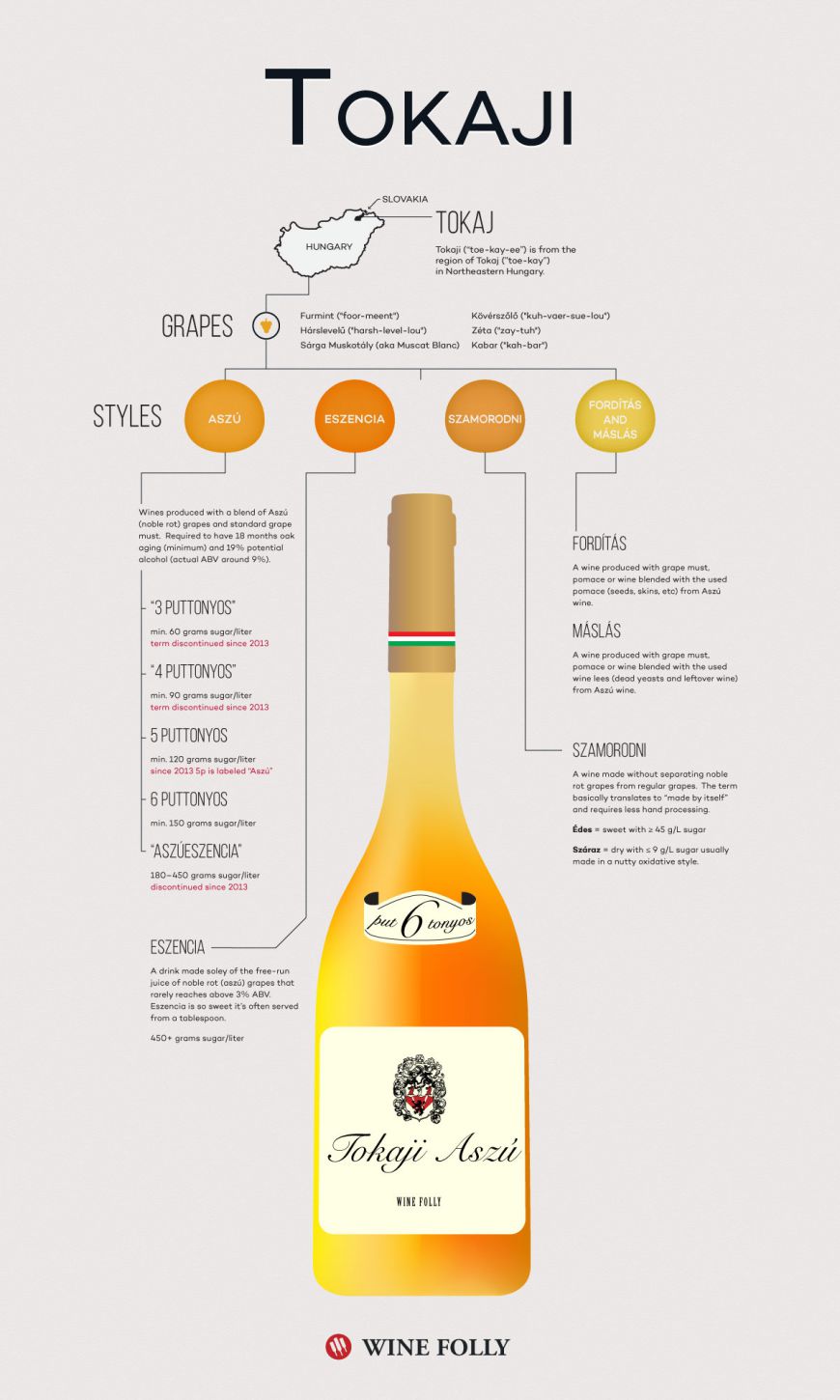

The wines of the Hungarian region of Tokaj, or as they say it “toe-kay,” are a window into the past.

Tokaji was once one of the most important wines in the world. A wine coveted by royal customers including Hungarian noblemen, Ferenc Rákóczi II, Peter the Great, King Louis XIV, Catherine the Great, and even Austrian composer Joseph Haydn (who received some payments in the form of wine).

The sweet wines of Tokaj provide the most compelling story of Hungary’s role in the modern history of wine.

The Story of Tokaji Wine

The most desirable of these elixirs (and the most expensive) was that of Tokaji Eszencia, a liquid goo that contains as much sweetness as straight syrup. It’s so intense that Eszencia is typically enjoyed from a tablespoon. Because of the high sugar content, it will age 200+ years.

Famous copycats

In Bordeaux, the weather along the Garonne River is dank enough to produce the same noble rot essential to the wines of Sauternes. In Germany, the Mosel River provides the same conditions that affect Riesling grapes that are now part of the classification of German Riesling.

In Alsace, France, and Friuli, Italy producers even donned the words “Tokay” or “Tokai” on their labels to capture buyers.

This confusion resulted in the classification of the vineyards of Tokaj in 1730, which lead to a noble decree, made in 1757, to establish the closed production district of Tokaj.

An example of botrytis on Oraniensteiner grapes (a cross between Riesling and Sylvaner) in British Columbia at Stoneboat Vineyards.

How it’s Made

The production of Tokaji Aszú and Eszencia is dependent on the development of a necrotrophic fruit fungus called gray mold, or botrytis. The mold develops on the berries in moist conditions (such as in foggy river valleys) and then dries when the sun comes out. This process of rotting and drying causes the grapes to shrivel and become sweet.

Additional flavor compounds also develop from the botrytis berries described as ginger, saffron, and beeswax. In Hungary, the grapes affected with this mold are called Aszú berries, and they are carefully separated from the rest of the grapes to be used in Tokaji production.

THE GRAPES OF TOKAJI

A wine can only contain 6 native varieties and still receive the Tokaji designation:

Furmint (“foor-meent”)

Hárslevelü (“harsh-level-lou”)

Kabar (“kah-bar”)

Kövérszölö (“kuh-vaer-sue-lou”)

Zéta (“zay-tuh”)

Sárgamuskotály (“shar-guh-moose-koh-tie” – aka Muscat Blanc)

This is where things start to get interesting with the traditions of Hungarian Tokaji production.

The Aszú berries were collected in large baskets called puttony and added in measured amounts to barrels of non-botrytis grape must. Then, the wines were produced and labeled based on how many Aszú baskets were added to the must. Thus, the system of labeling wines with ~3–6 puttonyos was developed.

The wine called Eszencia is a wine made entirely of Aszú berries. The grape must for Eszencia is so sweet, it’s practically syrup, making it very difficult for yeast to ferment sugar into alcohol.

It takes several years (usually 4 to 5 years) to fully ferment Eszencia (btw, this is similar to Vin Santo) Even with this long period of fermentation, Eszencia wines rarely ferment to over 3% ABV. Eszencia may be the lightest alcohol wine of them all!

A new era unfolds

Béres Winery redesigned its labels across its entire line of Tokaj wines. From left to right Omlás Furmint (a dry single-varietal wine from Omlás vineyard), Lőcse Furmint (a dry single-varietal wine from Lőcse vineyard), Naparany (a named wine blend that includes the Muscat variety), Diókút Hárslevelü (a single varietal wine from Diókút vineyard), Magita (a named blend late-harvest sweet wine), Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos, Tokaji Aszú 5 Puttonyos, Száraz Szamorodni (a dry style Szamorodni) and Tokaji Eszencia.

Today, several things have changed with the labeling and production of wines from Tokaj.

In 2013, the term puttonyos was technically abolished for Aszú wines (as we don’t use baskets to measure sugar levels anymore), and wines labeled as Tokaji Aszú are required to have a minimum of 120 grams/liter of sugar.

Producers may still use the phrase “6 Puttonyos” to signify an Aszú wine with 150+ grams/liter of residual sugar. Wines between 120–150 grams/liter of sugar are now labeled as Tokaji Aszú. Of course, you may see wines still labeled with 3 and 4 puttonyos for marketing reasons, but these do not meet the minimum sweetness requirement to be Tokaji Aszú.

Making a Name

Eszencia is now a segment of wine on its own (no more Tokaji Aszú Eszencia), with a minimum sweetness level of 450 grams/liter (this is, btw, 4 times as much as a can of coke!).

Finally, there is an entire new subset of wines emerging from the Tokaj region that are dry.

Dry single-varietal Furmint (“foor-meent”) and Hárslevelü (“harsh-level-lou”) have already made waves in the European markets and continue to gain interest. These wines usually have a touch of residual sugar (usually around ~7 g/L or only 1.5 carbs per glass). The residual sugar is there to counteract the intensely high natural acidity.

Even those the wines taste incredibly lean, and they’re often aged in neutral oak (in the local Hungarian oak!). Oaking this way adds a subtle body and texture to the lean, mineral profile of the wines.

Last Word

The reason we haven’t seen a lot of Hungarian wines (despite their former fame) has a lot to do with what happened during the communist regime. State-run wineries had little reason to focus on quality, and quality stayed low until the region began to privatize in 1990. Fortunately, with a strong winemaking tradition, we should hope to see great things from Tokaj and the other 21 regions of Hungary.