Notes on Attwood's Empire and the Making of Native Title

- 2 November 2021

- Celia Hay

That chance and circumstance...

Played such a central role in the foundation of New Zealand as a British colony is startling.

Professor Bain Attwood’s Empire and the Making of Native Title delves deeply into the records and original manuscripts of the imperial government and its officers as well as contemporary newspapers and commentaries from the 1800s. Attwood’s meticulous research exposes an extraordinary story for us to consider today.

Attwood shares light on the comparative differences between the colonisation of Australia and that of New Zealand. In 1769-70, Captain James Cook made claims to British possession of New Holland (largely to become New South Wales) and New Zealand on the basis of discovery. For New Zealand however, the British government did not formally act as if New Zealand was in their possession while in Australia, it commenced establishing penal colonies in 1788 and granting land to settlers on the basis that it was the only source of land title. The British government considered the Aboriginals had no rights to property or means to resist their colonial ambitions.

In contrast, Attwood argues, there were many examples, over the early decades of European settlement that demonstrate Māori as being sovereign over their land and domains:

…the British government, as a result of simultaneously disclaiming British sovereignty over New Zealand and implying that the islands were in its possession (by promising to protect the natives), had treated the New Zealanders over the course of the previous twenty years as though they were sovereign. [1]

All about land

One word could summarise the issues behind the decision of the British government to officially annex New Zealand in 1839: LAND. More specifically, land titles - who owned the land and who held the rights to sell it even if no one was living on a block of land or cultivating it?

The early explorers knew that New Zealand was a sizeable country with Māori settlements often found around the coast and large tracts of dense bush, hills and mountains largely uninhabited except during seasonal hunting and gathering (mahinga kai) expeditions. It was these vast areas of unoccupied land that was to attract prospective settlers and drive ambitious land speculators. This was considered waste land by many.

Principal players

Attwood sets the scene with a list of the principal players and it will be no surprise that there are no women and only one Māori chief in this line-up. There are names that we are familiar with: James Busby, Governor William Hobson, Rev. Samuel Marsden, Sir George Grey but what becomes apparent is there is a whole group of protagonists, still in Britain, who wield enormous influence from afar.

The New Zealand Company (formerly Association) with its plans for the systematic colonisation, based on the writings and leadership of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, became a formidable lobby group with its influential cadre of supporters in Parliament led by Charles Buller and the Earl of Durham (John Lambton) and sympathetic encouragement from some newspapers.

The CMS Church Missionary Society (Anglican) active since late 1814 when Reverend Samuel Marsden landed in the Bay of Islands from Sydney and the Wesleyan (Methodist) missionary societies who arrived in the 1820s were worried that their work of “Civilising and Christianising” Māori would be undermined. These groups strongly opposed the New Zealand Company’s plans.

The powerful Colonial Office through a series of Colonial Secretaries and their administrators, including those appointed to govern New Zealand, held a variety of changing views and their despatches of instructions would often take 5 - 6 months to reach our shores. Meanwhile, circumstances may have changed and instructions, out of date. The views expressed by these politicians and administrators were often at odds with those of the New Zealand Company, which in turn was exemplary in articulating its case, and subjecting these officials to public scrutiny and debate on the New Zealand problem. It is surprising from our purview to learn that three days were devoted to a debate on New Zealand in 1845 followed by another two-day debate a month later.

Port Nicholson Settlement

Early in 1839, the New Zealand Company learnt the British government planned to introduce legislation for the colonisation of New Zealand with the provision that no land could be purchased unless through the British government. In addition, it would not recognise earlier or direct land sales between Māori and Europeans. Wakefield’s response was to advise the Association to send off an expedition to buy land as soon as possible.

“Possess yourselves of the soil and you are secure, but, if from delay you allow others to do it before you, they will succeed, and you will fail.” [2]

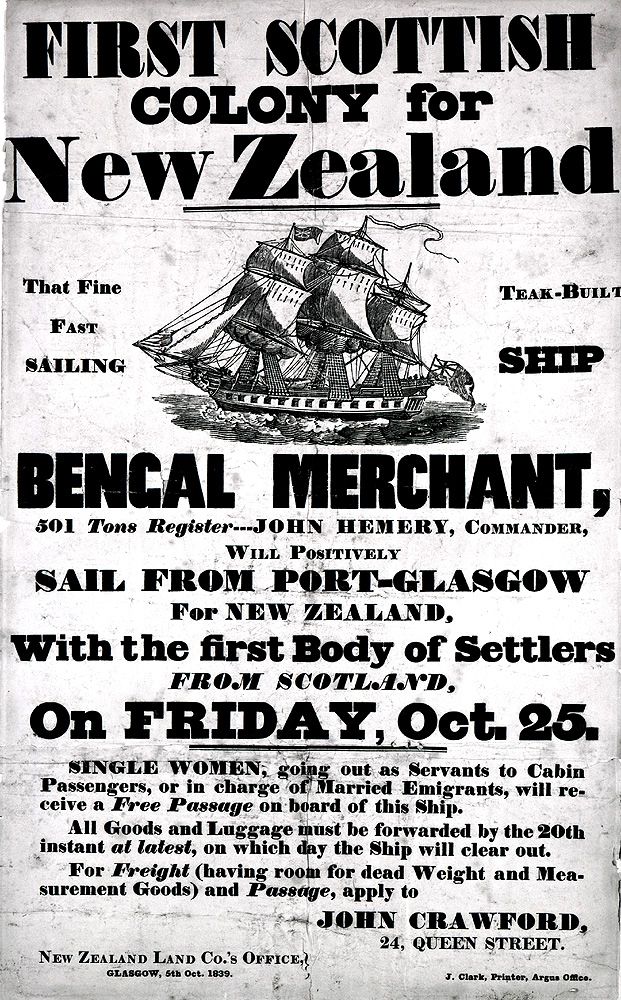

Advertisement for the Bengal Merchant; sailed from Glasgow, October 1839

The New Zealand Company then launched a publicity campaign publishing articles, taking out advertisements as well as holding public meetings to promote the new settlement of Port Nicholson (later Wellington) in New Zealand without authorisation of the British government. They offered land orders of one "town acre" and 100 "country acres" at £1 per acre. There were no land titles to view or opportunity to review anything about the land. By mid-July, the first sections was fully subscribed.[3]

In May 1839, the ship Tory departed in haste for New Zealand to start buying land. Colonel William Wakefield, brother of Edward Gibbon Wakefield was in charge and joined his nephew, Edward Jerningham Wakefield. This forced the Colonial Office to act as only by assuming or acquiring sovereignty could the British government prevent land purchases by others. Captain William Hobson was instructed by the Colonial Office to make a treaty with the Māori chiefs. He sailed for Sydney in July arriving in December 1839 where took further instructions from the New South Wales Governor, Sir George Gipps. The Tory arrived in Queen Charlotte Sound on August 17 1839 and shortly afterwards sailed to Port Nicholson. Colonel Wakefield commenced negotiating with local iwi to buy land for the hundreds of settlers who were about to board ships for New Zealand.

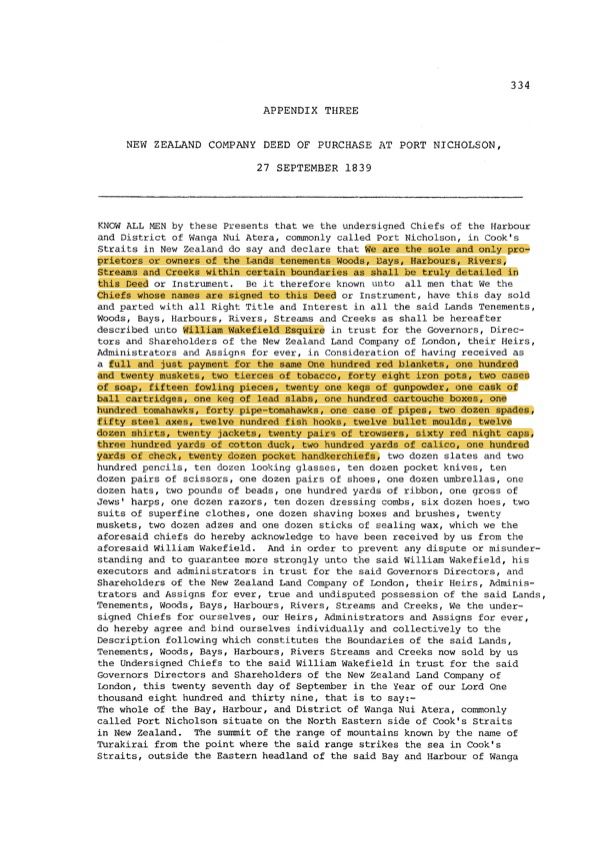

On 27 September 1839, upon the deck of the Tory, a deed was signed with Te Āti Awa and other rangatira for Port Nicholson and the Heretaunga (Hutt) Valley. Much of the payment was made in goods which were displayed (see deed below). On 25 October, Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata of Ngati Toa met with Wakefield. Ngati Hau chiefs signed for land between Manawatu and Patea. However, Wakefield's purchases were deeply flawed and while he purported to lay claim to 20 million acres by the end of 1839, he was warned that there would be issues. The Colonial Office refused to acknowledge these claims.

Traders and Missionaries

It is important to remember that Europeans had been active in New Zealand from the early 1800s especially in Northland. Various Ngāpuhi hapū (kin groups) were involved in provisioning whaling ships with water, potatoes and trading flax, whale oil, kauri spars and often supplying markets in Australia. Kororāreka (Russell) in the Bay of Islands became one of the biggest whaling ports, often hosting many ships from different countries, and overtime, developing a reputation for lawlessness. Māori also travelled to Port Jackson (Sydney) both as crew on ships and to trade. In New South Wales, Māori learnt about other cultures and gained new skills and technology to provide benefits for their hapū back home. Muskets became a symbol of power and along with other metal implements were highly valued. They also saw how the Aboriginal peoples suffered under British colonial rule. The Penal Colonies of Botany Bay, Norfolk Island and Tasmania were also instructive.

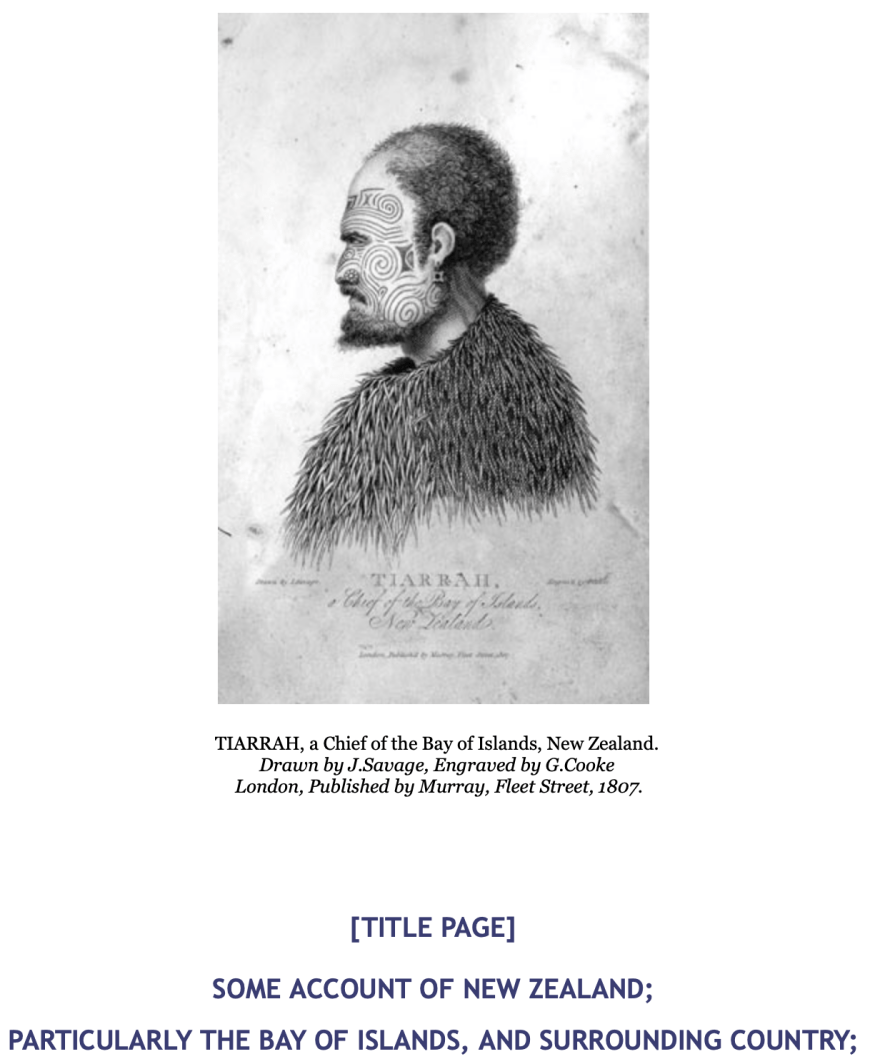

In 1805, chief Moehanga, a Ngapuhi ally, even ventured to London at the invitation of Dr John Savage, a surgeon on a convict ship who visited New Zealand. There is an outstanding record by Savage published in 1807 which describes many aspects of New Zealand life including aspects of diet (see below).

A steady stream of Māori, who crossed the Tasman, also visited Rev. Samuel Marsden's mission at Parramatta and some stayed on for many months. Ngāpuhi rangatira, Ruatara also travelled to London, with a goal meeting King George III and forging relationships, but was treated very badly on board ship. He met Marsden in London and then returned, staying at Parramatta for some months. This connection ultimately lead to a new CMS mission being established at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands, under Rautara's protection with the leadership of Rev. Thomas Kendall. The first missionaries arrived in 1814 with Marsden arriving just before Christmas and preaching the first Christmas service. In 1815, Marsden purchased 200 acres of land at Rangihoua confirmed with a deed of purchase.

After Ruatara's sudden death in 1815, Hongi Hika, who had also visited Marsden in Sydney, was eager to provide protection for the pākehā. Additional missions with schools were established on land controlled by Hongi Hika's hapū at Waimate and Kerikeri.

In 1820, Hongi Hika and Waikato travelled to London with the Rev Thomas Kendall to help with the compilation of a Māori dictionary at Cambridge University. They were presented at court to King George IV. While in England, Hongi Hika was able to buy muskets and technology and along with his relationship with pākehā, including the king, would strengthened his power over rival hapū once back in the Bay of Islands. Inter-tribal conflict amongst hapū created many tensions and utu (satisfaction, compensation) was often exacted.

This meeting with George IV would attain more significance over time along with the belief that there was a personal relationship between Māori with the British King. Worried about French ambitions for New Zealand, in 1831 a group of northern rangatira signed a petition asking George IV for protection. The growing lawlessness in the Bay of Islands prompted Marsden to recommend a British "resident" be appointed. In 1833, the Colonial Office appointed James Busby as resident and he arrived in the Bay of Islands with a letter bearing the insignia of George IV. Marsden and the missionaries not only regarded Māori as owners of the land but that they were sovereign and allies of the British Crown.

Pressure for colonisation

Back in England, Edward Gibbon Wakefield established the New Zealand Association in 1837 to promote the "systematic colonisation" of New Zealand. The New Zealand Association sought to protection Māori from the "aggression of British settlers" and to negotiate a treaty on the Crown's behalf. While this objective was not successful, as we can see from the commentary above, the New Zealand Association was prepared to act without government support. There was much debate on whether, as in Australia, Cook's "discovery" meant that the British Crown now owned the unoccupied, "waste" lands of New Zealand. While others regarded Māori as the customary owners of the land, with the ability to sell land to foreigners if they wished, opportunist land purchases of large areas were taking place.

The Governor of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps, who had now jurisdiction over the proposed new colony of New Zealand made an important proclamation. As William Hobson sailed for Waitangi in January 1840, Gipps warned land claimants that the Crown would not acknowledge the validity of any title that had been or could be acquired in New Zealand which was not derived from or confirmed by a grant from the Crown. This proclamation had significant ramifications for people who had purchased land or were about to purchase land from Māori. Te Tiriti o Waitangi was drafted and signed in the Bay of Islands in the early days of February 1840. It was then despatched by ship, around the country, for other rangatira to sign. While on February 12, Governor Gipps met a delegation of Ngāi Tahu rangatira, brought to Sydney by a group of entrepreneurs including John Jones later of Waikouaiti and William Charles Wentworth, a lawyer and politician from New South Wales, who wanted to purchase Ngāi Tahu lands. Gipps announced a commission to investigate land purchases and a Land Claims Bill that became legislation in August 1840. Four Commissioners would work to resolve land claims and titles from October 1840 - 1845 and William Spain, a lawyer from London, was appointed to look specifically at the claims of the New Zealand Company. The Protector of Aborigines for New Zealand would be present at these hearings.

The growing numbers of settlers, expecting titles for land they had purchased in Britain, started to voice their complaints in their own local newspapers, to Hobson, even holding a public meeting to have him recalled to London. In Port Nicholson, the settlers even formed a provisional government which Hobson regarded as "high treason". On May 21, Hobson declared sovereignty over all of New Zealand and in part to exert his authority. This was done before all of the chiefs had signed the Treaty. In July, the French ship Aube, arrived in the Bay of Islands to discover that the British had declared sovereignty. Bishop Pompallier had established a series of Catholic missions starting with Hokianga in 1838. Hobson's hastily dispatched HMS Britomart to Akaroa which arrived 5 days before the Nanto-Bordelaise Company ship, full of settlers, arrived on 17 August 1840. This averted the prospect of the South Island being claimed for France.

Crisis in New Zealand

In June 1840, 150 land claimants including Busby and Wentworth petitioned the New South Wales Legislative Council over the draft Land Claims legislation which was passed in August. The Land Claims commissioners had many claims to investigate and this process was slow and contentious. It was not helped by the death of Hobson in October 1842, the appointment of Willoughby Shortland as acting governor until the arrival of Captain Robert FitzRoy on 31 December 1843.

Attwood writes:

"Spain learned that many of the chiefs had never consented to the Company's purchases or signed the deeds, that some of those who had agreed to sell had never received a portion of the goods they had been promised and that many had not understood the nature of the transactions properly or the use and extent of the reserves they had been promised. Consequently, he recommended to Hobson that the Company only be granted a very small amount of the land it had claimed in Port Nicholson...." [4]

In 1844 a Parliamentary Select Committee was established to inquire into the state of the New Zealand colony with committee members dominated by New Zealand Company supporters. They strongly argued the company's case with the objective of changing government policy regarding land titles. In June 1843, 22 people had died at Wairau over a dispute with Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata over the purchase and subsequent survey of land. After Governor FitzRoy criticised the motives of the settlers and failed to take action against Te Rauparaha, agitation started to have him recalled and replaced.

“..beginning in 1844-45, the New Zealand Company used its considerable political power in Britain to persuade many members on both sides of the House of Commons to adopt its point of view about native title and the Treaty. They had long argued that the colony’s crisis was caused by the Tory government wrongfully construing the Treaty as guaranteeing native possession of all the land in New Zealand and that the solution to the colony’s problems lay in the establishment of a property regime that limited the rights of property the natives could claim to the lands they cultivated.” [5]

In July, the Colonial Secretary, Lord Howick's report on the Select Committee findings was tabled in Parliament with recommendations. The following year, after much pressure, the House of Commons debated the New Zealand question: the state of the colony and case of the company, for 3 days and put to vote the resolutions from the 1844 Howick Report.

"Many of the speeches... were highly erudite, which was partly a function of the fact that an enormous amount of material pertinent to the debate was readily available in printed parliamentary papers. This is turn was a consequence of the enormous political contestation that had taken place over sovereignty and native title in regard to the colony over the preceding five or six years." [6]

While the vote was lost, the New Zealand Company claimed a victory. In July, a second debate took place over 2 days with Charles Buller's motion lost 89 to 155 votes. In a despatch dated 30 April 1845, FitzRoy was officially relieved of duties as Governor although this was not received by him until until 1 October 1845. The new Governor, George Grey arrived in New Zealand in November 1845 with funds to purchase land cheaply.

"He proceeded on the basis that Maori had rights in all the lands and their title to it was best extinguished by acquiring their consent. Hence native title was finally made in New Zealand…(and) largely the result of a long and halting historical process that had been dominated by enormous political contestation and conflict..." [7]

Attwood goes on to conclude that the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown did play a role in the making of native title. This came into being only as the result of deeply historical processes, which were rarely linear in nature but halting, contingent and ultimately reliant on a large degree of chance. [8]

Celia Hay 6/11/2021

Footnotes

[1] Attwood, Bain, Empire and the Making of Native Title: Sovereignty, Property and Indigenous People, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2020 p.134

[2] ibid, p.128.

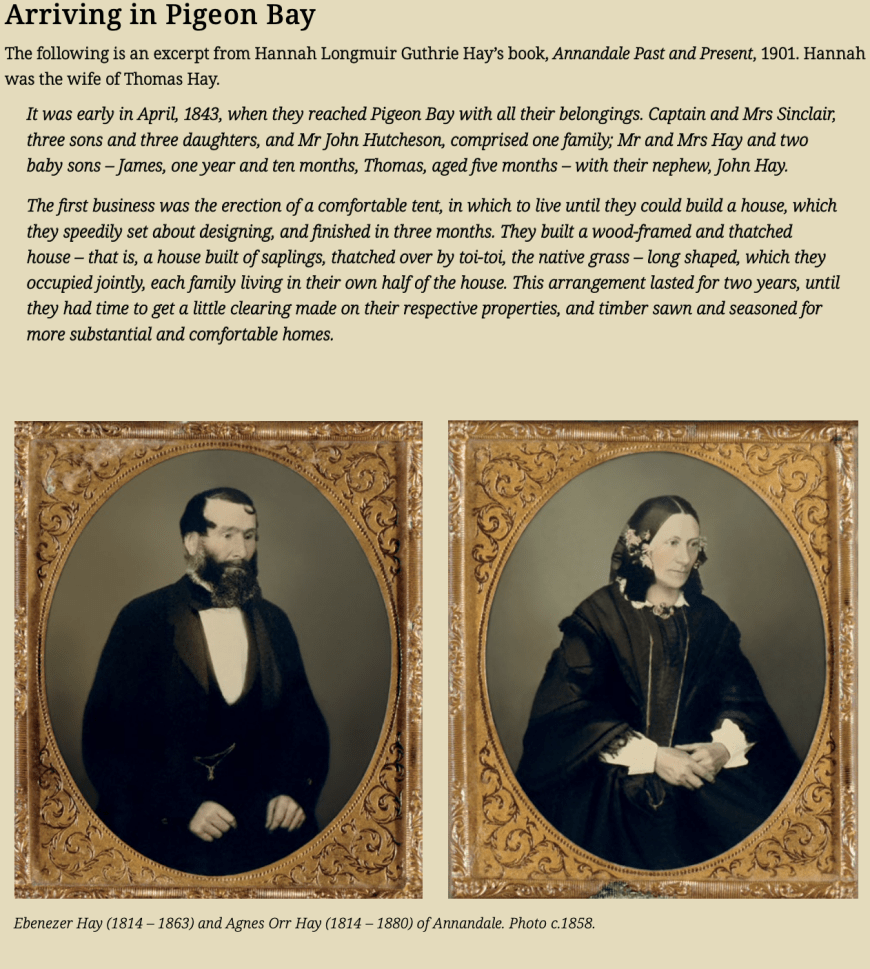

[3] A Dr Francis Logan convinced Ebenezer Hay and Agnes Orr, his wife of three days, to emigrate to New Zealand. Dr. Logan had previously travelled to New Zealand as a doctor on a convict ship and spoke positively about the country. He also emigrated with his wife and family on the Bengal Merchant. There were 120 passengers and the passage took 104 days to D’Urville Island in Cook’s Strait. Only two people died en route. Ebenezer Hay paid £200 for 200 acres and after failing to secure land in Port Nicholson, in April 1843, the family sailed to the South Island to squat on land in Pigeon Bay, Banks Peninsula. In 1851, the family finally obtained title for this land. (Hay Family letters to Scotland. See excerpts below - these were returned to the family in Pigeon Bay in the 1880s).

[4] ibid, p.127

[5] ibid, p.12

[6] ibid, p.320

[7] ibid, p.12

[8] ibid, p.405

Take a look

In 1807, Dr John Savage writes about trading potatoes:

"Though the natives are exceedingly fond of this root they eat them but sparingly, on account of their great value in procuring iron by barter from European ships that touch at this part of the coast. The utility of this metal is found to be so great, that they would suffer almost any privation, or inconvenience, for the possession of it; particularly when wrought into axes, adzes, or small hatchets: the potatoes are consequently preserved with the greatest care against the arrival of a vessel."

"The likeness I took of Tiarrah was so striking, that it gained me a great degree of popularity among the natives, and many of them came a considerable distance to see it; several offered to accompany me to Europe, and I selected one, whose countenance pleased me, for the purpose of bringing to England. He was a healthy stout young man, of the military class, and connected with families of the first consideration in these parts." - Savage.

Click below to see the digital copy of this book

Dr John Savage, Some Account of New Zealand; Particularly the Bay of Islands, and Surrounding Country London 1807

More on Potatoes:

"THE inhabitants of this part of the world are by no means unskilled in arts and manufactures: among the former is their cultivation of the ground. This, it is true, is confined to the growth of one vegetable, but which they are remarkably successful: I allude to potatoes; and indeed I never met with that root of a better quality: they keep remarkably well, and we provided a stock of them sufficient to supply the whole ship's company for several months." ibid, p.54

"And here it may not be improper to remark, that in my opinion no kind of food taken to sea has a greater tendency to preserve the health of a ship's company, or to recover it from the effects of a long voyage. I think I have observed more benefit derived in cases of scurvy from eating the root raw with vinegar, than from any other remedy: it appears to be most efficacious if taken in the morning fasting.

I could not learn when they first became possessed of this invaluable root; they have, however, had some opportunities of changing their seed, which has been of great advantage to them. Cutting is not in practice, the smaller potatoes being always preserved for seed." ibid p.55

About Moehanga: "...accompanied me to London, and furnished me with much information concerning his country during the time he remained with me; I found him a most affectionate kind-hearted creature, and parted with him reluctantly: a favourable opportunity occurring in a few weeks after my arrival for his return, with Capt. Skelton, of the Ferret, South Whaler, who I knew would treat him with the greatest kindness...The ample stock of tools he took with him would render him superior, in point of riches, to any man in New Zealand; and there is not a doubt but the example of his success will induce many of his countrymen to try their fortune, whenever an opportunity for emigration may offer."

The canoe containing his kindred came alongside, and as soon as it was made fast to the ship, Moyhanger's father came on board. After a little preliminary discourse the father and son fell into each others arms, in which situation they remained near twenty minutes, during which time the right eye of the father was in close contact with the left eye of the son: abundance of tears were shed, and a variety of plaintive sounds uttered on both sides. The venerable appearance of the father, who is of their religious class, made the scene truly interesting.

After spending some time in Sydney, he returned to his home in the Bay of Islands in March 1807. He was still living in the Bay of Islands in 1827.

Deed of Purchase at Port Nicholson Page 1

I have highlighted some of the goods that formed part of the purchase payment for Port Nicholson (Wellington). This page is from H.H. Turton, Maori Deeds of Land Purchases in the North Island of New Zealand, 2 Vols. (Government Printer, Wellington, 1878), Vol. 2, pp. 95-96. in Tonk, RV, 'The First New Zealand Land Commissions 1840-45', MA Thesis, University of Canterbury, 1986

Letters from Ebenezer and Agnes Hay

29th October 1839 (From the Bengal Merchant)

1/4 hour from 7 o'clock

Dear Parents

I embrace this early opportunity of writing you a few lines to let you know how we are getting on. We have just risen from an excellent dinner. We are retired into our own cabin and is very comfortable. Agnes is busy making curtains for our hammock. They are getting ready our tea. 10 minutes to 10 o'clock we have just risen from a sumptuous tea. We have this morning engaged a girl to clean our shoes and soap out our cabin. She appears to be a hardy creature. She is a native of Ayrshire and is going out without a single acquaintance going with her. Mrs Hay and I is just relieved from a promenade on deck before breakfast. We are much delighted to see our company in so good spirits about going away. We have just risen from a great breakfast - mutton chops and potatoes, beef steak and rice curry and loaf bread and tea. Are living in hopes to sail at 2 o'clock It is our prays and hearts desire that God will be with us all unto death and over it and after it and that He may be with us all through time and through all eternity. The steam boat is alongside of us to take away which we were wearing very much for we have a fair wind and expect to be out sight of land by tomorrow morning.

Excuse haste, we remain dear parents your affectionate children E and A Hay.

20 February 1841

Petone

My dear Parents

….We had a pleasant passage. We landed in 110 days. We remained three weeks on board and three days on board the Glenbervy. Mr and Mrs Logan and I Ebenezer Mr Wilson, Mrs Yule, Mr Wallis ever on shore putting up the houses. Ours is very comfortable... roof and walls are thatched the vent and floors are made with clay. I wash them with the same and they are the [colour] of your parlour, our clothes were hole damaged our food is porridge and milk broth and potatoes the biscuit and scone. This climate is much like Scotland but not so cold in winter. Eben has sown a few seeds they are doing very well.

We had several earthquakes since we arrived here, the first shook our bed so much that it wakened us in a fright. Mr Logan hearing us said it was an earthquake. Eben thought it was a man under the bed shaking it. The others were not so bad. The natives are not frightened for them, they have them frequently, we are not afraid of the natives they are clever intelligent people, we are much in want of a Pastor here. We are like sheep without a shepherd…

Dear Parents, although far separated in the meantime we may yet meet if not in this world I hope in the next. O Remember us in your Prayers.

Eben has got his town land it is far back we are waiting on the country land if it is not good we intend going to another part of the Island. We are eight miles from the Town as they changed it since we arrived. Eben is working at Wellington. He is making 10/- per day fencing in ten acres. I sleep alone all week but Saturday and Sunday. I also sew a good deal…

My dear Mother. I had a premature Birth in the 7th month, a daughter, she lived on 23 days. It pleased the Lord to take her and we must not grumble He took but what He gave. I did not put up the curtains, the weather being so warm.

Dear Parents, I remain your affectionate daughter

Agnes Hay

O do write us.

Find out more

Attwood, Bain, Empire and the Making of Native Title, Sovereignty, Property and Indigenous People, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2020

Te Puni Kōkari - Map of Iwi

Te Ara Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

National Library of New Zealand